(CNN) – The recently discovered Flame virus bears all the hallmarks of a cyberattack concocted by a nation-state. It’s big and complex and pointed directly at a geopolitical hot zone, Iran.

What really gives it away as a government project is the extent to which its programmers sought to keep it out of civilian hands. The malware seems no more designed to protect us from a nuclear Iran than it is safeguarded to keep us from using the program itself against one another.

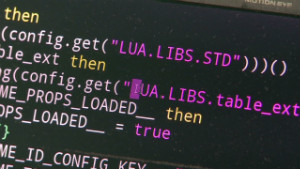

Flame is sophisticated. It’s not a tiny piece of code that nests itself in e-mail and then erases your hard drive. It might better be described as a suite of programs – the Microsoft Office of malware – that perform different tasks.

One turns on the microphone of a computer to record conversations; another sets up a virtual machine on the computer to be controlled remotely; another uses Bluetooth to connect to nearby cell phones and copy data or monitor phone calls. One compresses all this espionage into smaller files; yet another sends data back to the master computer, accepts commands and installs new updates. This level of complexity and breadth of functionality is unparalleled.

But, in the theater of cyberwarfare, every successful cyberattack can be considered the most advanced attack of all time. This is an arms race of a new sort, where measures and countermeasures change the entire programming landscape. The methods of previous attacks, once analyzed, are neutralized by new additions and patches to computer operating systems. This sends would-be infiltrators back to the drawing board to come up with new, superior approaches. Technological warfare is a bit like evolution, where new mutations compete for survival.

Only on computers, we don’t have to wait for nature to spontaneously fold a chromosome in some new way. We have programmers actively looking for new windows of opportunity, new maneuvers, new countermeasures and new ways of hiding what they’re doing.

It amounts to the weaponization of cyberspace – a practice in which the U.S. government has apparently been participating, sometimes reluctantly, according to an article in The New York Times last week. The cyber campaign against Iran apparently began under the Bush administration working with Israel, and continued under Barack Obama, who voiced concern about the precedent America was setting.

The resulting Stuxnet virus, aimed at disabling Iran’s nuclear refineries, ended up getting loose on the Internet in the summer of 2010. The revelation of U.S. involvement with the virus worried Obama, according to the Times article, as it could justify future cyberattacks on Americans by enemies of the United States.

Flame may or may not be another product of this same campaign.

When asked about his nation’s complicity in the malware, Israeli Vice Prime Minister Moshe Ya’alon cheekily told Army Radio, “Israel is blessed with high technology.” But the rest of us are blessed with high technology, too.

What’s to keep malware such as Flame from being used against civilian populations or even by civilian populations?

Nations have been using computers for warfare since computers existed. The development of the modern computer was in no small part accelerated by World War II. America’s ENIAC computer calculated artillery trajectories, while Britain’s Colossus computer decoded the Nazi’s encrypted messages. At the time, however, computers were not household appliances. Like cannons and other weapons of war, they were tools of the state and inaccessible to regular folks.

And while the current cyberwar may be a nation vs. nation affair, the kinds of technologies unleashed in this conflict are not beyond the technical capability of more rogue hackers and criminals. The same technologies that let the U.S. and Israel thwart Iran’s nuclear program can also enable, say, an Eastern European crime syndicate to participate in your banking activity.

What makes Flame unique – and almost certainly of government origin – is that it appears to have been written in a way that not only slows detection and countermeasures, but that also slows the spread of its techniques. The complete suite of programs is over 20 megabytes.

And while at first glance this seems to be a downside – an elephant hiding in plain sight – it has actually served to keep it unnoticed for at least two years. More importantly, it was made huge on purpose. Much of its code is simply camouflage – 3,000 lines of programming that make it hard to understand and even harder for an enemy team of coders or even hackers in the civilian population to copy and use themselves.

It’s as if its programmers were attempting to be responsible or at least exclusionary, and to prevent the weaponization of the greater Internet. Now that’s classic government behavior. It’s also probably futile.

Such efforts will likely only slow this inevitable slide toward an Internet that feels as blocked by security checks as an international airport. For in truth, we are all blessed with high technology.