Back around the turn of the century, I wrote an article for Adbusters called “The Sabbath Revolt.” I was arguing for a “one-seventh rule” where we reserve one day a week for non-commodified activities. This idea of a day off each week was one of the first things the Israelite slaves gave themselves after escaping from Egypt. And seemed to me it could serve as a safeguard for the coming digital onslaught. If the algorithms and AIs were really going to program us into a new sort of slavery, perhaps withholding 1/7th of our time from them could give us enough pause to reflect and reset on our inherent worth.

The article got me a lot of attention, particularly from Jewish organizations dedicated to keeping the religion going. They were all concerned about declining membership in synagogues and Jewish day schools, and thought someone like me could help them bring Judaism into the era of MTV and the World Wide Web. “Digital Shabbat” might catch on, they suggested.

In speaking with them, though, I realized that most of them didn’t really understand what Judaism was all about. They had mistaken it for a religion — for a set of things to believe in. At least as I understood it, Judaism was originally meant as the way to get over religion. It was a set of practices developed by people who had just suffered through the death cults of the pharaohs. Their mythical patriarch Abraham smashes the idols and instead worships a more abstract, universal God, who slowly recedes and eventually disappears — leaving human beings alone to take care of one another and all living things.

For me, the spirit of the whole enterprise was captured in the image of the very first ark that the Israelites build in the desert (the one that shows up in Indiana Jones). It was just like the ones they had built as slaves in Egypt, except—unlike all of those—there was no statue of a god on the top. Instead, there was an empty space, protected by two cherubs facing one another. The idea was that God shows up in that empty space between two people, really engaging face to face. The “nothing” between us is truly sacred.

So I wrote a book called Nothing Sacred, looking at how this essential insight was surrendered to the practicalities of maintaining a peoplehood, particularly in a world where you’ve been exiled from your homeland and need to get along as a perpetual immigrant. Interestingly, the book got me banned by a few of the Jewish philanthropies who depend on fear of intermarriage, assimilation, or threats to Israel for donations.

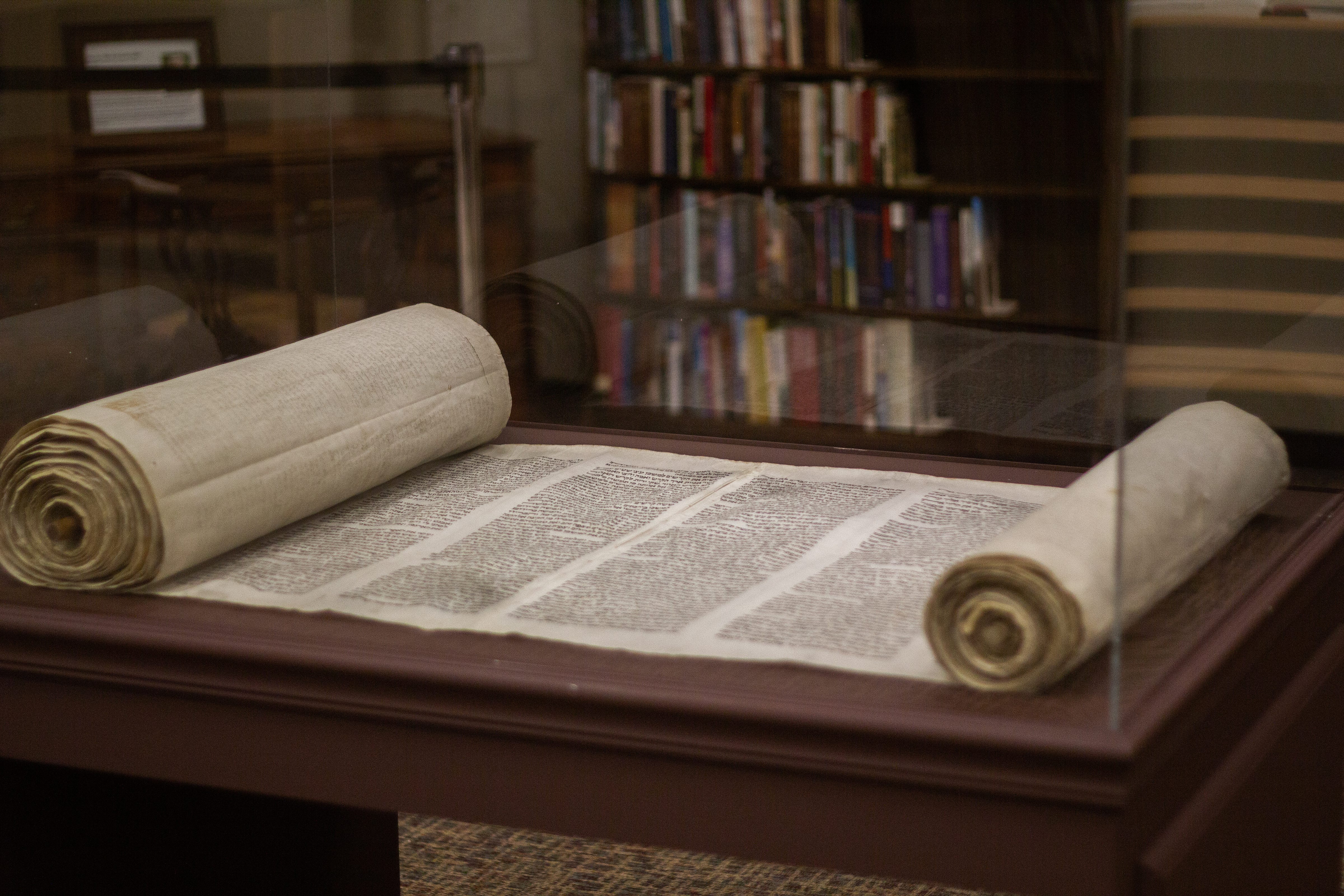

What worried them most, however, was that if people started looking at the Torah as an open source proposition up for interpretation, then its role as a land deed would be undermined. If you want to use the Torah as proof of title on Israeli real estate, then you can’t also leave its meaning up to the interpretation of each generation who engages with it. But by denying this exploration, you prevent Judaism from renewing itself.

They accused me of threatening Jewish continuity, but I saw them as a threat to the greater Jewish project — the real continuity of discussion, intepretation, and re-invention. That’s what keeps any tradition alive: continual change, and perpetual refinement. Nothing is too sacred to be questioned and reflected upon. Judaism is powerful enough to stand up to such scrutiny, playfulness, and inquiry. If only those responsible for its institutions had enough faith to let this anti-dogmatic tradition do its thing, it would attract thinkers and seekers, social justice advocates, and intellectuals alike.

As I see it, Judaism is an invitation to participate in a multi-generational project of negotiating nothing short of a just civilization. It’s the original open source tradition, where a simple demonstration of literacy — the b’nai mitzvah—earns one a place at the table. Then, like any posse of hackers, we argue over the code for the rest of our lives.

How well Judaism retrieves these core insights may be less important than whether other institutions are able to do so. Constitutional democratic government, in particular, requires an ongoing, robust discussion of its purpose and function. But to do that, we have to achieve basic literacy in civics. Just like a Jewish kid studies Torah and learns to read Hebrew, would-be participants in democracy must study civics and learn the classical and Enlightenment philosophies that brought us democracy—especially if they mean to challenge them.

We don’t read in order to submit. We read in order to be fit to write, ourselves.