In John Carpenter’s B-movie classic, “They Live”, donning a pair of special glasses allowed humans to see the hidden programming in the media all around them. Messages from alien overlords, such as Art is Terrorism or simply Obey were revealed to be hidden in billboards and magazine covers.

See, it wasn’t the ads people knew about that were the problem, but the ones embedded in the landscape. They were nested in the very fabric of reality—so much so, that they were rendered invisible to the naked eye.

Ubiquity is the persuasion professional’s best friend. The more embedded a medium or message—the less like an identifiable thing it appears to be—the more it becomes accepted as a pre-existing condition of nature. It’s not a message at all; it just is. Less a piece of content than a platform. Like Facebook.

That’s what Marshall McLuhan was getting at with his famous line the medium is the message. A smart phone, for example, isn’t just a tool for getting email and phone calls. The device in your pocket creates an environment around itself—a new set of behaviors and assumptions about how we socialize, earn money, and make meaning.

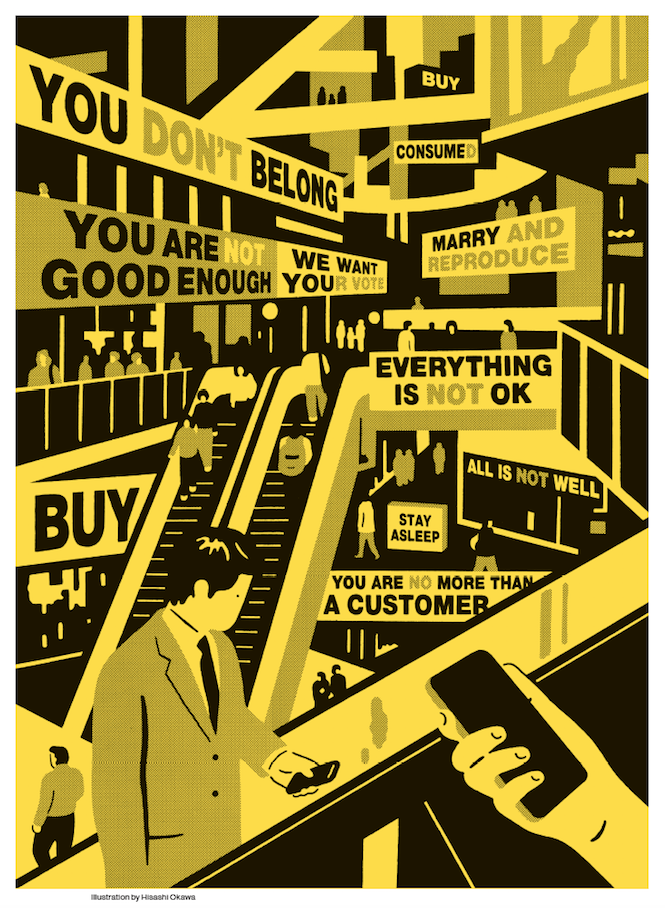

However manipulative the methods of a salesperson or advertisement, I was always more frightened by shopping malls and the web. Sure, a well-trained auto salesperson can fool or intimidate me into paying more than I should—but at least I know where the enemy is.

When I walk into a shopping mall, I’m not so aware of the way the entire environment has been crafted to make me a more compliant consumer. The floor plan is designed to disorient, forcing me to use store signs as anchors. The music, smells, lighting, and ceilings are all optimized to induce Gruen Transfer—a slack-jawed and impulsive state named for the architect of the first shopping mall. The environment itself does the work.

The online world is just such an environment. Once users have stumbled onto a website, they may as well be inside the mall. Every background, button, color, and cue has been optimized to induce a particular behavior—from making purchases to uploading an address book.

The one defense mechanism most of us have online is that going online is a conscious choice. Even when the web is accessed through an app on an iPhone, there’s a sense of crossing through a portal: the feeds and streams are on the other side of the glass. At the very least, we have some subconscious awareness that these are synthetic worlds, optimized to exploit us.

What happens when these platforms migrate from our devices into the real world? Well then, we may as well be living in the shopping mall, or in the Disneyfied Times Square. It’s a mixed-media reality, where any wall may turn out to be a billboard, any sound a Pavlovian cue, or any person a role-playing avatar.

And clicking to get more information about any of these things will turn up whatever sponsored explanation has bid the highest at that particular moment. The task of decoding the landscape will be impossible, since there will no longer be any terra firma through which to gauge the level of abstraction or manipulation on which we are operating.

Think of it like waking up in an advertisement, or inside a video game where the only way to win is to accept the underlying premise of the game designer. When media is ambient, it’s no longer simply part of an environment—it is the environment.

At least for the time being, when we’re not sure if there’s a message embedded in the landscape, we can always take the glasses off. Once these technologies are embedded out there in the world, the code they’re running may as well be the laws of nature.