I was running late for class last week, so I hopped in the car and drove to the closest parking lot I could find to the CUNY Journalism School, which turned out to be up on the roof of the Port Authority bus terminal. As soon as I arrived up there and saw the sky and the parked cars, I realized I’d been there before.

All of a sudden, a rush of memories washed over me. This was the same place where my grandfather parked his Cadillac that day back in 1972 when he brought me along to watch him do his rounds ordering fabric in the old garment district.

My mother’s father had one of those typical, grand, rags to riches immigrant stories. Literally. He was the oldest son of a successful fishmonger in Romania, but when the Jews were for bidden from fishing in Galatz, his father sent him to America to start a business and raise enough money to bring the rest of the family across.

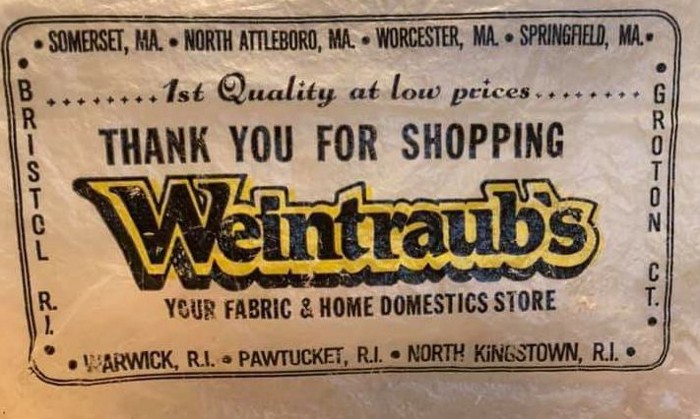

So, a 14-year-old Morris Weintraub boarded a ship, got ill on the voyage across, but was allowed to recover at Ellis island until he was well enough to take care of himself. He sold rags on the Lower East Side until he had enough money for a cart, then a whole shop, bringing over relatives with the profits until all five brothers and two sisters, and their parents were in America, and “Weintraubs” had grown into a chain of nine discount fabric stores from Groton, Connecticut to Worcester, Massachusetts.

The labor of the business was distributed between the brothers. Morris was the boss and buyer — a mythic figure in our family — so I was suitably thrilled when he invited me to accompany him on his day to sample and purchase inventory for the stores.

I met him at 6am outside his apartment building in Riverdale, where he was already waiting in his orange Sedan deVille. “You’re ten minutes late!” He shouted out the electric window. “I almost left without you!” (It was my parents fault, but he said that was no excuse if I was going to get ahead in this life.) We arrived at the Port Authority, which he said was the cheapest lot in the area, and I got my tour of a city behind the city.

We’d go into a fabric store, then up the back stairs to set of offices. Or we’d go down and alley, into a side door and up a freight elevator. We’d arrive at generic old office with tables or desks and some other 60-something bald Jewish guy would smile to see Morris, offer him a drink as if seeing a friend from the old country (maybe he was), and then bring over a few bolts of fabric or Post-it size swatches for my grandfather to sample.

“29 cents a yard,” the guy would say.

Morris would rub the sample between his fingers and say something like, “Eh, it’s not a weave it’s a print,” and then offer 19 cents. The other guy might counter with 25 cents. Then grandpa would say “how about 22 for 5000 yards?” Done. (“Volume talks louder than price,” he’d explain to me later.) Then they’d both make a note on their little pads. That’s how business was done.

On and on like this, all day, from Seymour’s to Sammy’s to Lenny’s and eventually lunch at Horn & Hodart’s “automat” cafeteria on 38th street. “I used to be able to get a steak, potato, coffee and a piece of pie here for fifty cents.” Impossible, but his own memories of old New York, like mine, may have less to do with the numbers than the spirit.

Yet as I rushed to class last week, parking in as close to the same post as I can remember from fifty years ago, went down the very same elevator, and walked by some of the very same “to the trade” fabric shops that still dot the streets of the garment district, I wondered what was going on upstairs in those old offices. The windows were no longer etched with “Goldmans Imports” or “Cohen Fabric Distributors,” but I spotted a few hair salons, real estate offices, an immigration service, and some sort of IT company. I imagine all that back-room haggling over fabric prices happens online, if at all, and businesses the size of Weintraubs have been been trounced by conglomerates.

Still, I felt connected to the city and its history in a way I hadn’t before. No, I didn’t take over the family business, but neither had I truly ventured so far from what Morris did or where he did it. I was just another generation, walking to work on the same sidewalk, to go upstairs in the old Herald Tribune building and haggle over headlines and topic sentences with journalism students the way he did over thread count and cents-per-yard with his merchants. It’s all part of a joyful game — more an excuse to engage, and a way of keeping the whole organism running as beneficially for everyone as possible.

If Morris Weintraub taught me anything about business, it wasn’t just to buy in quantity for a discount, but that our relationships are everything. They’re not just a means to an end, but a reason to get up in the morning, drag oneself into the city, and — when necessary — pay for parking.