We are not in a second industrial age. That may be the dream of those who really want to double down on the dehumanizing legacy of the past few hundred years of employment. But the emergence of digital technology, algorithms, and robots offers much more than an opportunity to further automate our businesses, alienating our workers and customers alike; it’s a chance to retrieve the human sensibilities at the heart of our organizations, and embrace the truly collaborative, participatory spirit of this age.

The digital renaissance of the early 1990s was about the unbridled possibilities of the collective human imagination. Early internet pioneers understood that human beings, connected as never before, could create any future we wanted. Unlike passive television viewers, members of the internet generation would be more hands-on participants in the world. Instead of the conformist and highly individual “company man,” we’d begin to see teams of creatives, developing new approaches from the bottom up. Armed with a PC and an internet connection, anyone could become anything.

Such a future felt too unpredictable to most businesses — and especially to investors, who are betting on those futures. The digital future became stock futures — from a thing we create together, to a winner-takes-all, zero-sum competition. The business world valued predictability over possibility. In such a landscape, humans are valued not for their creativity, but their utility — how does each one influence the bottom line?

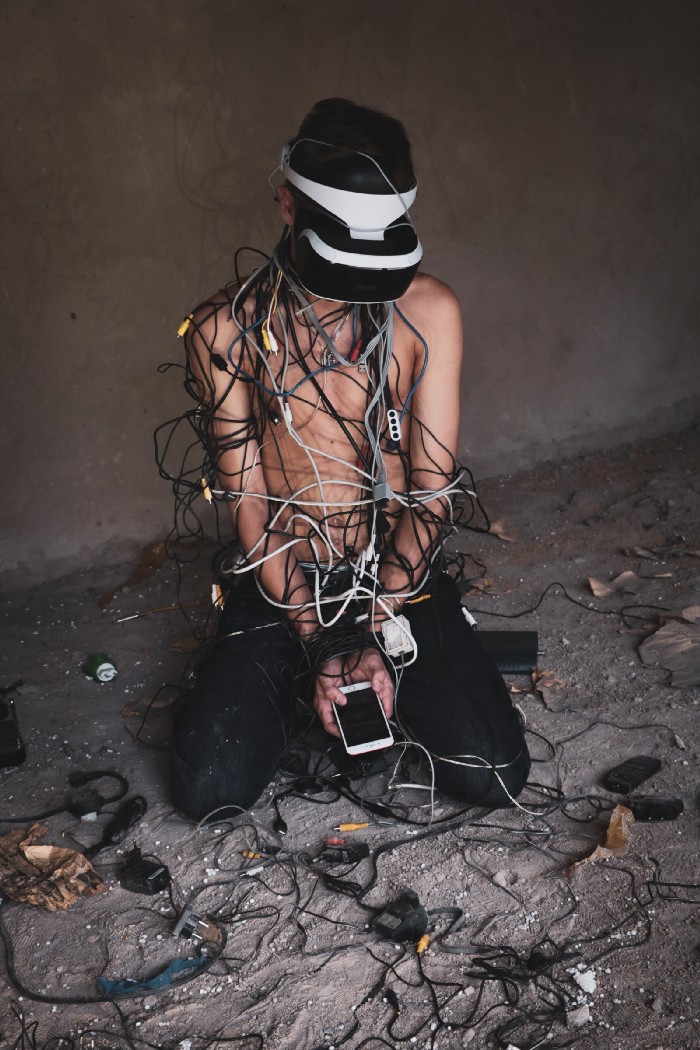

And so digital platforms were configured to repress creativity, connection, and novelty. Think of the “auto-tune” function that changes a singer’s pitch to make it land exactly on a quantized note. Does it make the singer better, or simply more exact? What if we auto-tune James Brown or Billie Eilish? We lose all evidence of them reaching up for the note, or coming down over the note. We lose the humanity. Our digital approaches are treating this character as “noise,” when it’s actually the signal.

Likewise, we’re looking at our employees as machines to be tuned and optimized rather than human beings to be unleashed.

The original industrial age

This is not entirely our fault. We’re still simply following the playbook written for us back in the late Middle Ages, when employment was actually invented.

This was a period of tremendous growth. Europeans returned from the Crusades having opened up new trade routes and brought back new innovations from other lands. One of them was the “bazaar,” which became the European marketplace. The former peasants of feudalism started producing and trading things on their own, using local currencies that functioned a lot like poker chips. The money was rendered worthless at the end of the day, or cashed in for grain or whatever commodity it represented. In this fledgling, peer-to-peer economy, the peasants became the new middle class.

It was great for everyone, except the aristocracy, who were losing control over the economy. So they came up with two ways of stopping the party. They made local currencies illegal. Everyone would have to borrow money, from the central treasury, at interest. (This meant the economy would have to keep growing, even to this day.) Second, the “chartered monopoly” made it illegal for anyone to do business other than those few merchants chartered by the king. The independent shoemaker would now have to become an “employee” of his majesty’s royal shoe factory — or be jailed for illegally competing with the monopoly. Employment was born.

That’s when the clock went up on the highest tower in each city. Instead of selling the value they created, workers were now selling their time. And instead of hiring the most competent craftspeople, companies hired the cheapest laborers they could find. Mass production and the assembly line were not invented to make production faster or better; they simply allowed companies to hire untrained workers, who were taught one tiny stage of the process.

Mass production meant that branding and marketing would soon be the main way for companies to distinguish their products from each other. Branding became less a way for companies to communicate their processes and competencies, but mythologies invented to hide the reality of their factories from consumers — Keebler Elves baking cookies in a hollow tree.

The competence crisis

I got a call from the CEO of a U.S. television manufacturer, asking me to help him bring his company culture to life. I happen to know that there are no TV manufacturers in America, so I asked him to clarify. “Well, we don’t actually make the TVs…” he admitted. But neither did they do the design, fabrication, logistics, or even the marketing. They were essentially running a spreadsheet of outsourced competencies. They were a ticker symbol, and little more. He wept with me in his office as we searched his company directory for anyone who actually knew anything about televisions, around whom we could build a company culture.

Too many companies think this way. They follow the approach to business modeled by CEO Jack Welch in the 1980s, who discovered that GE made less money manufacturing and selling a washing machine than they did lending money to a consumer to purchase the appliance. So they sold off their appliance business and went almost entirely into financial services. Then came the recession of 2007, and the company has yet to recover.

Instead of selling off core competencies and the devaluing people who hold them, companies must learn to cherish and protect them. This suggests a very different sort of org chart for a company — one based less on seniority or proximity to the C-suite than competence. Less of a tree than a mandala, with concentric rings of competence. Who are the true geeks of the company’s competency? The nerds who are most into cement, dog food, bicycle tires, mortgage refi, or whatever it is your company offers? They are the ones at the center. Each successive ring is occupied by those who are supporting those in the center. Management is just a form of “customer service” for the aficionados in the middle. Just outside the company’s outermost circle are the consumer superfans of the company — the folks who would do anything to get inside and see how the company really works.

When you have a company based in competence — true, nerdy passion — then unsolicited resumes begin flying in. You are recognized as the center of your industry, because you embody the industry’s culture, in the flesh.